Why am I writing about this?

In Germany, we are currently witnessing an uprising. A growing resistance from the center of society against right-wing extremist tendencies in society and politics. After reading Bastian Allgaier‘s touching blog post about his grandfather’s Nazi past (which he unfortunately deleted), I thought to myself that I absolutely had to write about the history of my grandfather on my father’s side.

A story that can only be told here “second-hand” and consists largely of hearsay. Because I was only 7 years old when my grandfather, my “Opa” (grandpa) as I called him exclusively, died. A story of coming of age during the Weimar Republic, about a family in Nazi Germany during the Second World War, a story of the “resistance of the little man” and a story of civil courage. But also a story of opportunism and indifference.

Who is my grandfather actually?

I don’t know much about my grandfather. I only know first-hand that I liked him very much. He was a very quiet, reserved and modest person. He was helpful and always offered my parents to look after us children, me and my sister, so that they could run errands or even go on vacation. He loved skiing, motorcycling and especially my grandma’s cooking, but also dishes from Yugoslavia, which he had learned about later during the occupation. He loved nature and animals, especially horses and his shepherd dog Kuno, whom he had trained himself as a dog handler for the police service. My grandparents lived in the apartment above us, so I had the privilege of growing up together with my grandparents. To me, my grandfather looked a lot like Stan Laurel. Whenever I watched Stan and Ollie movies later on, I was very reminded of him. He often took me and my sister for walks when we were little and pushed us around the village where we lived in a baby carriage. He took us to a nearby farm where horses grazed in a paddock and he let us children stroke them and feed them with apples and sugar cubes. It was thanks to him that I had the amazing experience at the time of a horse licking a sugar cube out of my hand with its warm, moist tongue and leaving a sticky trail on it, similar to a snail.

My grandpa didn’t talk much. He observed and stayed in the background. He often slept on the sofa in the living room at lunchtime. He was probably very exhausted from the horrors of the war, as I later explained to myself. The war had not yet been over for 30 years. He never talked about it, especially not to his underage grandson. He had no directly visible war injury, but had become hard of hearing from a bomb attack. You always had to talk to him very loudly, which my grandmother in particular did. And he loved us, his grandchildren, very much. We couldn’t think of anything better than to disturb him at nap time, poke and tease him and pull his hair to get him to wake up and play with us or go out into nature. He never took offense or got upset. He was always a haven of peace for me and had a calmness that I wish I had inherited from him. As my mother always emphasized, he was a kind-hearted person who died far too early without me really getting to know him. So I can only really access my grandfather’s stories through the stories of others. But through research for this article, I found documents about my grandfather’s life that shed more light on what his life was like from the 1920s until the end of the war.

How does one become a Nazi? A biography of the early 20th century

My grandfather was born in 1904, came from southern Germany (Bubesheim near Günzburg) and grew up in simple circumstances as an illegitimate child in rural areas, which was certainly not easy at the time. His mother moved with him to the Ravensburg region. In October 1922, at the young age of 18, he enlisted in the police force for 12 years. 1934 was therefore an important year for him, as his employment contract expired at that time and a decision had to be made as to whether or not he could continue to be employed in the police service. He married my grandmother in the summer of 1929. From the time the Nazis came to power in January 1933, the police service was strictly controlled by the Nazis, as was every civil service. In the documents I looked through, there is a reference to the fact that my grandfather joined the NSDAP (Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei) on May 1st, 1933, specifically the “Kameradschaftsbund der Polizei“, translated to “comradeship association of the police”. I only found out about this while researching this article, although I had always suspected this, as you couldn’t be a policeman in the German Reich at that time without also being an NSDAP member. You could only get promotion opportunities or basic permission to be employed by the state if you were a member of the NSDAP party. However, mere membership on paper does not, in my opinion, make him a Nazi without further ado.

Civil courage

A story that is told again and again in my family at least suggests that my grandfather did not lose his inner compass despite being a Nazi. Although I can’t say exactly when this happened, it was at least after the Nazis came to power and probably before the war. My grandfather was still a police constable in the municipality of Baienfurt in the district of Ravensburg and ran the police station there. His area of activity also included the small farming village of Köpfingen. One of the farming families had a mentally disabled boy who lived on the family farm. My grandparents knew this family. As part of the preparations for the mass murder of physically, mentally or emotionally disabled people, known by the Nazis as “Aktion T4“, children who showed “abnormalities” at birth that indicated a disability had to be reported to the relevant health authority. My grandfather, as the holder of police authority in the village, would also have had to report the disabled boy of the farming family to the health authority as a so-called Lebensunwertes Leben, translated to “life unworthy of life”. However, he defied this requirement, helped the family to hide the child on the farm and concealed its existence. This meant that the child was able to avoid sterilization or even being killed by the Nazis and survived the Nazi regime.

Later, in times of hunger or food shortages after the war, the farmer family often provided my grandfather’s family with food and supplies in return. Unfortunately, contact later broke off. A few years ago, my parents, who used to visit a local restaurant in the village of Köpfingen, told this story to the owner of the restaurant. He told them that the disabled “boy” was well known in the village and had recently died as an old man. This brings me full circle, which at least makes me feel reconciled about my grandfather’s Nazi past.

The Second World War

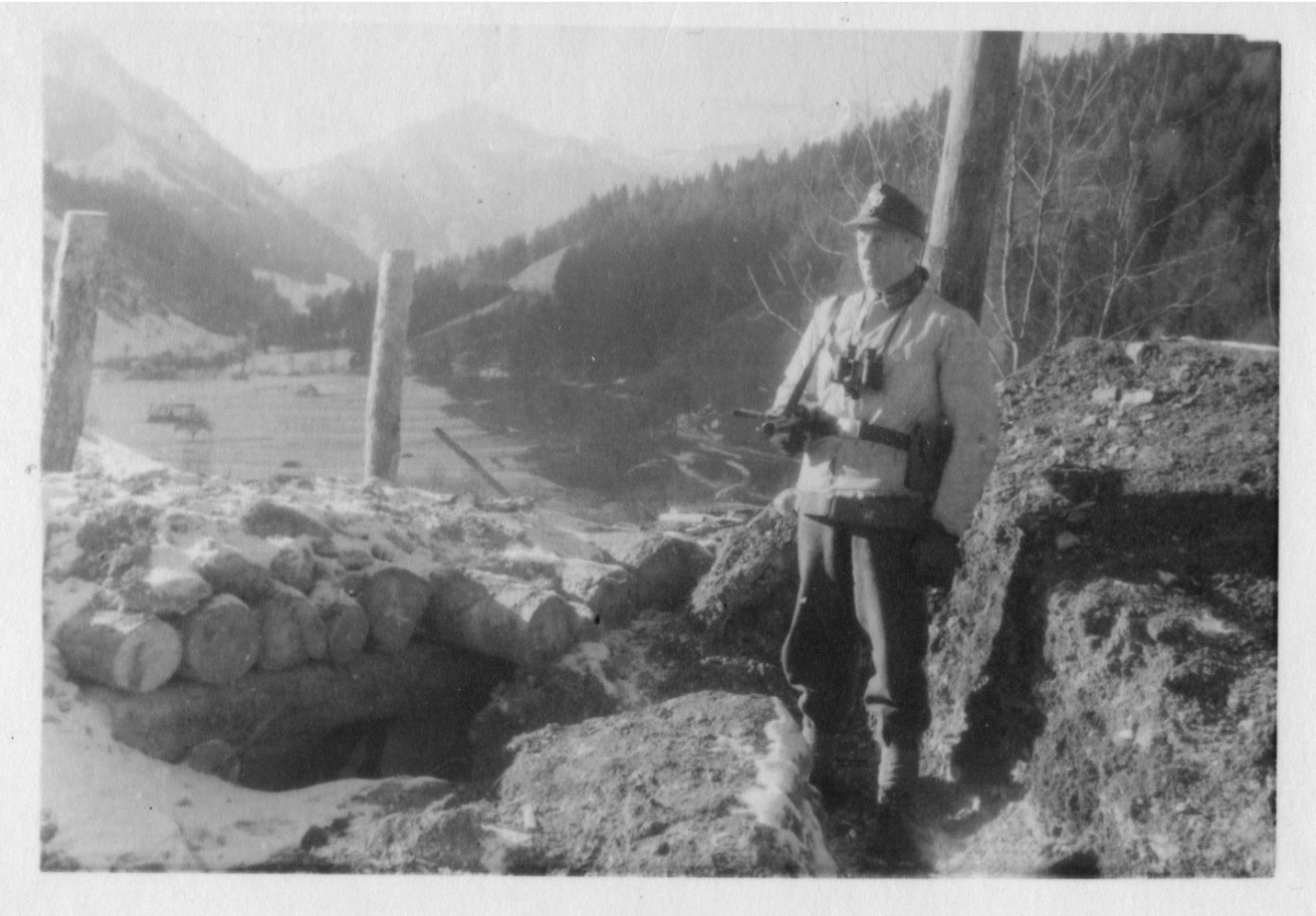

But the story doesn’t end there, because my grandfather was drafted into military service, initially as a “Gebirgsjäger” (mountain infantryman) and towards the end of the war he was stationed in Yugoslavia. The multi-ethnic state there had just collapsed in the Yugoslav Civil War from 1941 to 1945, a time of upheaval, collaborators, spies and subversives, a time that made it difficult to know who was on which side. Yugoslavs fought alongside the Wehrmacht against other Yugoslavs in the communist People’s Liberation Army under Josip Tito. My grandfather also fought side by side with Yugoslav soldiers against other Yugoslavs, mostly communist partisans. Whether the friendly troops came from Bosnia, Croatia or Slovenia is no longer possible to say exactly. And my grandfather also made friends with the Yugoslavs. As collaborators, the German occupiers repeatedly had to fear attacks from partisans, including my grandfather and his comrades.

There are precise details in the documents. My grandfather was stationed in Krainburg (now Kranj) in Oberkrain (now Gorenjska) from January 6, 1943 until the end of the war and manned the gendarmerie post in the municipality of Eisnern (now Železniki) in what is now Slovenia. While he was stationed there, one of the friendly Yugoslav fighters wanted to take his wife to safety from the approaching Tito partisans, because as Nazi collaborators he and his wife had to fear execution or severe sanctions. Through his connections, my grandfather made it possible for his wife to escape to the German Reich and stay with acquaintances in his home near Friedrichshafen. The partisans were currently planning an attack on the post where my grandfather was stationed. Today, it is no longer entirely clear what exactly happened. But legend has it that the friendly Yugoslav was able to persuade the partisans to attack the post only after my grandfather had left it. Whether through bribery or some other deal is unclear, but many German occupiers were probably killed in this attack, but my grandfather was spared thanks to this intervention by his friend. Later, towards the end of the war, my grandfather was not so lucky.

War injury and escape

The post where my grandfather was stationed was attacked by partisans on November 21, 1944 and blown up with a bomb at 3 o’clock in the morning. My grandfather was in the building at the time and a wooden beam fell on him, seriously injuring his head and causing him to faint. When he regained consciousness, he realized that he could no longer hear anything in his left ear. He fled from Eisnern and a troop doctor diagnosed an injury to his left eardrum and a fracture to the base of his skull. My grandfather only received full medical treatment in Klagenfurt on November 28, 1944. He was then transferred to Laibach (today Ljubljana). There he was also diagnosed with hearing loss in his right ear due to an injury and slight paralysis. He then spent the rest of the war in a convalescent home in Velden am Wörthersee. These events shortly before and after his war injury are documented in detail in the records, as he later had to prove exactly how the injury occurred with witness statements and documents for his retirement. It has to be said that during the German occupation of Yugoslavia, there were frequent atrocities against the civilian population and enemy soldiers. Of course, I can’t say whether my grandfather was involved in this. In any case, there is no proof, neither can any proof be found in the documents.

However, there is also no proof of this, but my parents keep telling me that he returned home by foot from the war. From Slovenia or south-eastern Austria to south-western Germany is perhaps not a very long distance. Google Maps today says it was a 5-day walk, but he still had to cross the Alps on foot in the turmoil of the end of the war. This is another story that I would have liked to have heard from him in full detail.

The friendship with the Yugoslavian ally and his wife continued even after the war. The Yugoslav family often visited my grandfather’s family and my grandfather traveled to Yugoslavia a few times. He loved Yugoslavian food very much and often went to the Yugoslavian restaurant in his home town. When the Yugoslavian family came to visit Germany, they always had dinner there together. A beautiful side-story of a friendship that arose from such a terrible event as the war. It was a story that I always enjoyed being told, because it showed my grandfather as an upright man who fought for the wrong cause on a large scale, but had civil courage and attitude on a small scale, and partly did the right thing.

Rehabilitation?

The folder in which I found the confirmation of my grandfather’s NSDAP membership also contains a curious letter from the “Staatskommission für die politische Säuberung, Land Württemberg-Hohenzollern” (translates to State Commission for Political Cleansing, State of Württemberg-Hohenzollern) dated August 1948. To explain: My grandfather was elevated to the status of “civil servant for life” in August 1939 and was therefore officially a civil servant. After 1945, people who were obviously working in the civil service were examined and (rarely) sanctioned as part of the denazification process. The letter from the “State Commission for Political Cleansing” states:

It is decided and announced in the cleansing case: The person concerned [my grandfather] was a simple nominal member of the NSDAP. He did not belong to any of the organizations declared criminal by the Nuremberg Trials [e.g. SS (Schutzstaffel), Gestapo (Geheime Staatspolizei), etc.]. The person concerned supported the National Socialist regime only insignificantly and is a follower.

Is this now the official rehabilitation, even if it is not particularly meaningful as such? Because today we know that such commissions were very lax in their treatment of Nazis and criminals. In the French occupation zone in particular, where my grandfather also lived, persecution and punishment were handled extremely laxly. So no, this is no rehabilitation.

To this day, of course, I know nothing at all about my grandfather’s inner motives. Unfortunately, because I would very much like to discuss them with him personally. But a certain opportunism is evident in all these documents. They show that he was promoted in June 1933, one month after joining the party. I believe with a fair degree of certainty that he was never interested in political participation or even an affiliation with Hitler or Nazi ideology. After all, he never spoke about this time as particularly glorious, worthwhile or honorable. He never spoke about it to my grandmother, my aunt (his daughter) or my father (his son).

Ultimately, I believe that as a young man under 30, he simply wanted to continue his 11-year career in the police force in order to be able to support his young family. My aunt was born in August 1933, so my grandmother was already heavily pregnant at the time of the decision to join the National Socialist Party. And if he had resigned from the police force or been suspended without a party membership, he would have found it difficult to gain a professional foothold in the crisis years of the early 1930s. But these are just speculations, without wanting to justify this behavior. But perhaps an attempt to fathom and understand my grandfather’s inner justification.

The written confirmation that my grandfather was a member of the NSDAP – in other words, a Nazi – was certainly a turning point for me. This is the proof, in black and white. Although I secretly expected nothing less, based on his biography, which I already knew. But I can now empathize with this decision and understand it to a certain extent. And unfortunately, I have to admit for myself: I would probably have made the same decision, which moves me a lot and still does to this day. Because I could have answered the frequently asked (or perhaps too rarely answered) question to the grandparents’ generation myself “How could all this (the Nazi regime) happen?”: I would have fallen into the same trap back then under these circumstances.

However, knowing the perfidious logic of the Nazi regime today, would I still do the same if, for example, the AfD (the German extreme right wing party Alternative für Deutschland) were in government? The answer would be a clear “No”. The only question today is at what point you have to leave this country or enter into open and perhaps violent resistance against a fascist regime.